For eighty years, Britain has been trying to live up to this promise: "Build the homes the nation needs." For those same eighty years, governments have fallen short.

Britain became the nation that stopped building. The cost is paid not just in rent and mortgages, but in productivity, mobility and generational fairness. We used to understand homes were as vital to national wellbeing as hospitals, railways or energy grids, though. So, how did we end up setting smaller targets and still missing them?

The BRIK-Down

Since the end of World War II, governments have set various targets for housebuilding. Despite the initial drive of a massive public housing programme in the 50s, we've since seen decades of dwindling housing.

If Britain had sustained the building rates of its most successful era, millions more homes would exist today. The affordability crisis would look radically different, and so would patterns of inequality, productivity and mobility. Instead, delivery has continually lagged behind need, widening the gap vto historic proportions.

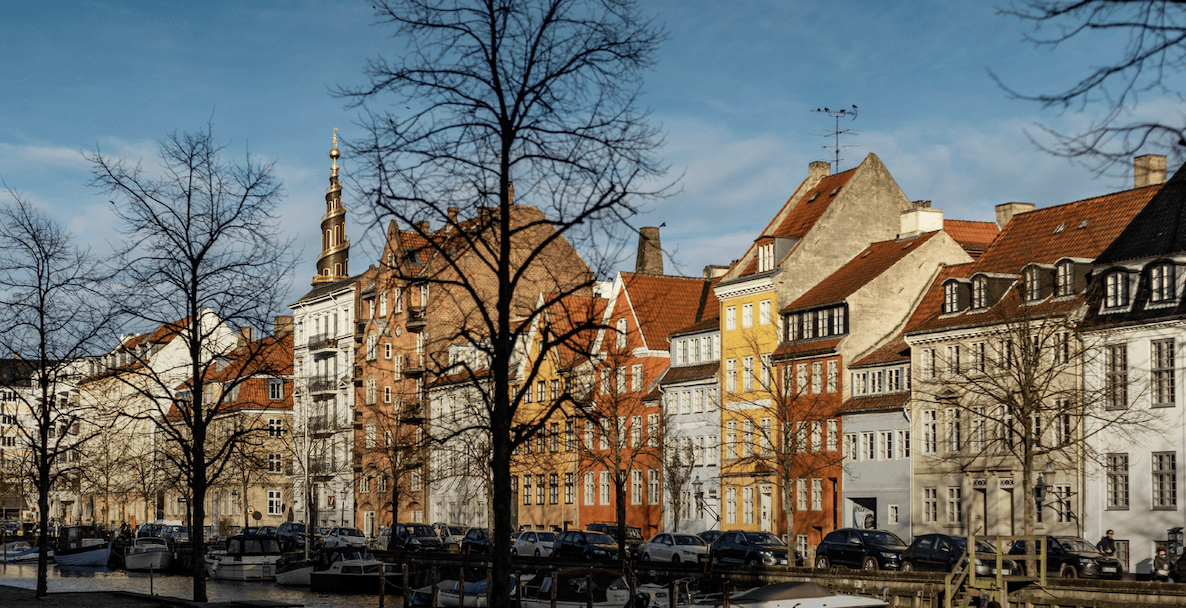

The Underbanks restored

It may feel like the Underbanks star has risen again swiftly, but the revival has actually been a long game. It all started with recognition of the street's heritage back in 1974, when it was designated a conservation area. But the next real breakthrough came in 2017 with a £1.8m National Lottery Heritage Fund grant that began seeing cobblestones relaid and façades revived. The Stockport Mayoral Development Corporation has since injected millions as part of its £1bn regeneration of Stockport town centre - bringing the original history back to its best and vacant buildings back to life.

Where Missing the Mark Started

Before we dive into where the problem began, let's look back at a period when ambition did match delivery. The post-war years were the last time Britain treated housing like true infrastructure.

A moral and economic mission of national recovery, in 1951 Winston Churchill's government pledged to build 300,000 homes a year. The homes were modest, the technology simple, but that target wasn't just met, it was exceeded. Throughout the early 50s, completions averaged well above the initial pledge, powered by state-led construction.

And all amid rationing and austerity. This era created one of the fastest and most equitable expansions of housing stock in modern history.

In 1966, Harold Wilson's manifesto reset the goal at 500,000 homes a year. By 1968,

Britain had reached around 416,000 completions, still the highest recorded annual total according to the Office for National Statistics. This success was all down to government-led building, streamlined planning and political unity around a shared mission. But this momentum didn't last.

- 1970s - inflation, political change and a retreat from public building.

- 1990s - targets shrank even as demand soared. The system lost the muscle memory of how to build.

- 2000s - Labour's 2007 Green Paper set the target at 240,000 additional homes a year in England by 2016, only to be derailed by the financial crash. Though it was met briefly, only once, in 2019/20.

- 2010s - in 2019, the Conservatives adopted a familiar benchmark: 300,000 homes a year in England. Again, to remain unmet, with net additions between 221,000 and 234,000 per year.

To buck the trend and meet our current target of 1.5 million homes over five years, we'd need sustained annual delivery of around 300,000. Is that an operational reality? Our track record wouldn't suggest so.

A Growing Nation, Shrinking Ambition When Britain last built at record scale, the national population was about 50 million. Today, it stands at around 68 million (and is projected to exceed 72.5 million by 2032). That means 20 million more people, but roughly 150,000 to 200,000 fewer homes built each year.

Early indicators for 2024/25 show some renewed activity, but not the step-change needed. Why?

Honestly, we've created a system almost designed to fail at scale. Planning is complex and adversarial, from local resistance to under-resourced authorities.

Private development cycles are short-term and profit-sensitive. And political hesitation means governments go with targets over the machinery capable of delivering them.

Our Take

Even hitting the elusive 300,000 a year now would only stop the problem getting worse, not solve it. And if we don't want to carry the crisis through another 80 years, it's no longer enough to crawl closer to our goals; we actually need to start exceeding them.

By paying attention to the post-war successes, we know what works: sustained public investment, empowered delivery bodies, land reform and a planning system that enables scale instead of strangling it.

We need to change course, and rebuild homes as real infrastructure, brick by brick. Before we fall further behind.